Behaviour-Based Safety – Part 2 | Habits

Previously, we ended on how BBS combined with management’s commitment and direction can gain safety buy-ins throughout the organization. Without management support – especially senior management — the task of creating a new safety regime can be very difficult since a management’s biggest health and safety responsibility is to drive objectives and goals. It starts with a collaborative, systematic identification process that captures the most common safe behaviours and then standardizes them throughout the organization. Behaviour Based Safety works best when you take a systematic approach to capture data, examine the motivation behind the data, and harness it to increase desirable behaviours.1 However, most procedures ‘die out’ after a while; if not regularly kept up, they become less attractive and less effective, with no routine to reinforce the process. One way to ensure that workers perform safe procedures regularly is to make safe routines into habits.

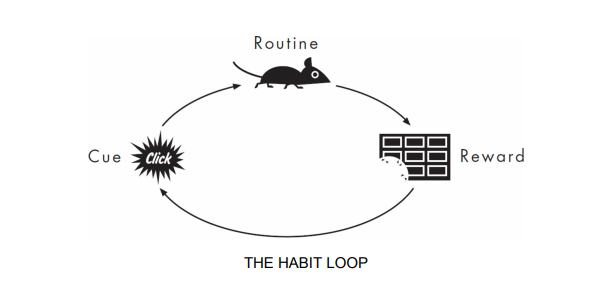

Habit Loop

So, what are habits? Before we delve into habits, we need to know how they are formed. Charles Duhigg, an award-winning author of The power of habit: why we do what we do in life and business, believed that habits emerge because the brain is constantly looking for ways to save effort. The brain, when left to its own devices, will try to make almost any routine into a habit because habits allow our minds to ramp down more often.2 Although conserving mental effort is tricky because if our brains power down at the wrong moment, we might fail to notice something important, we can get seriously injured. Our brains are programmed to scan for specific triggers or cues to save effort and that tells the brain to go into rest or automatic mode.

We can do two things with habits: ignore them or change and/or replace them. Ideally, changing unsafe habits is preferred because we form safer habits by creating habit loops. The brain’s dependence on automatic routines can be both beneficial and dangerous. In manufacturing, since most tasks are repetitive, habits can form quickly, without an in-depth analysis of the task. In most cases, it is left to each worker to assume safe routines to do their job. If tasks are not carefully observed and regularly analyzed, adopters may easily adopt bad habits that could eventually lead to serious injuries.

Make Safety a Habit

It takes a lot of effort to make safety habit changes in any organization. One easy way to create small wins in staff unsafe behaviours is to develop keystone habits. Charles Duhigg introduced this idea that “Typically, people who exercise, start eating better and become more productive at work. They smoke less and show more patience with colleagues and family. They use their credit cards less frequently and say they feel less stressed. Exercise is a keystone habit that triggers widespread change.” Some examples of keystone habits that you can implement in your workplace are safety, people, accountability, and organization.

An easy way to implement keystone habits is to include them as a consistent part of each employee’s workday—it needs to be part of the daily routine, not something that is done only after an incident, after a safety meeting, or when being observed. Safe habits ensure that people do the right thing every time without thinking about it. 4 Charles Duhigg developed a four-step to change unsafe habits and replace them with safe habits.

- Identify a routine

- Experiment with rewards

- Experiment with Triggers

- Create a plan to change the unsafe routine.

We start by asking what the triggers for unsafe behaviours are: location, time of day, emotional stress, mental states such as boredom, physical states such as fatigue, presence of others or action performed. Then we start by identifying the reward; is it temporary relief from stress, boredom, or fatigue. Is it a distraction, is it the satisfaction, or is it saving time? As you can see, many triggers and rewards could play a part in our habits, so we shouldn’t simply jump into a routine and try to break the habits cold turkey. It is crucial to observe triggers and rewards for weeks or months, note the three common reasons (rewards) that come into mind for that unsafe habit, and gradually eliminate the reward.

A common belief is that it takes 21 days to form a new habit. Unfortunately, it is not that straightforward, and that statement is missing a few words. One study on changing habits found that it takes a minimum of 21 days to form a new habit. Subsequent research has confirmed that the 21-day mark is often a best-case scenario and that the median timeframe for habit formation is 66 days (Lally, van Jaarsveld, Potts, et al., 2010).[1] Once you establish the standard behaviour, it can take up to 66 cues, routines and rewards to formulate a habit.

In 2002 researchers at New Mexico State University wanted to understand why people habitually exercise. In one group, 92 percent of people said they habitually exercised because it made them “feel good”—they grew to expect and crave the endorphins and other neurochemicals a workout provided. In another group, 67 percent of people said that working out gave them a sense of “accomplishment”—they had come to crave a regular sense of triumph from tracking their performances and that self-reward was enough to make the physical activity into a habit. In other words, other than financial rewards, employers must think of other rewards for employees to reinforce new habits or existing habits at the workplace. Here are some ways you can indirectly encourage safer habits:

- Recognition (verbal/written praise, birthdays, Employee Appreciation Day, work anniversaries,

safety accomplishments, safety performance reviews) - Involvement (include in decision making processes, voting, surveys, sharing responsibilities)

- Personal Development (Training, setting personal development goals)

- Continuous Improvement (Evaluation of reward systems, Safety goals & KPIs)

The first rule in creating safe habits is to break the old ones and choose the desired safe behaviours we want. Suppose we wish to build a habit of stopping and dealing with potential hazards in the workplace before they become incidents and near misses. In that case, we must identify the potential cues and rewards and plan to replace those triggers and rewards. As we saw, finding a correct cue and reward for a specific routine can be time-consuming, experimental and requires discipline. But don’t forget this investment in time and effort can save a life.

THE GOLDEN RULE OF HABIT CHANGE

You Can’t Extinguish a Bad Habit, You Can Only Change It.