Behavioural-based safety | Part 4: Safety Culture

by Pourya Ghani

The previous articles in this series outlined how to develop a behavioural-based safety program and ways to use tools such as observation and feedback to establish safe behaviours. But before designing your behavioural-based safety program, don’t forget to consider the importance of a safety culture with shared values. We need to establish these patterns of safe behaviours to have a thriving safety culture.

What is a Safety Culture?

“The safety culture of an organization is the product of values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies, and patterns of behaviour that determine the commitment to, and the style and proficiency of, an organization’s health and safety management. Organizations with a positive safety culture are characterized by communications founded on mutual trust, by shared perceptions of the importance of safety and by confidence in the efficacy of preventive measures.”[1]

Of course, your organizational values must align with the fundamentals of safety; that is the first step in building a healthy safety culture. Then we must create a conviction to work safely to gradually win people’s hearts and minds.

The strength of your safety culture heavily influences employees’ beliefs and attitudes towards safety. Without a strong safety culture, there will be very little participation in safety initiatives—eventually leading to unreported incidents or near-misses, which in time can cause a serious injury. To prevent this, a clear leadership commitment to safety as the number one priority reinforces the need to immediately report unsafe acts or conditions and the belief that reporting a problem will lead to a solution.

The leadership commitment is proven to affect employees’ perception, belief and attitudes only when followed and reinforced by management and senior leadership. If just one “critical” corrective action is left incomplete for too long, or a manager ignores someone behaving unsafely, employees quickly lose faith that the company is serious about safety. In turn, this demotivates employees to comply with safety rules since management doesn’t “walk the talk.” So, if we know that management’s behaviour can vastly impact employees’ perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs, then which safety culture model has behavioural safety as its core pillar?

Cooper’s Reciprocal Safety Culture Model

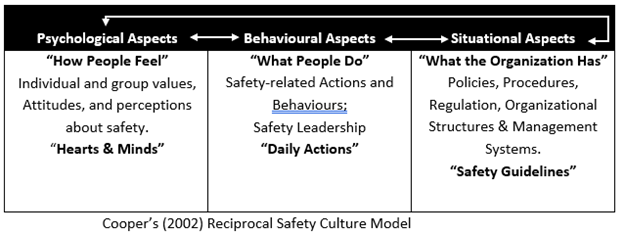

One of the prevailing safety culture models of the 21st century is Cooper’s (2000) Reciprocal Safety Culture. This model shows the reciprocal relationship between employees’ perceptions and attitudes towards safety goals and day-to-day directed safety behaviours.

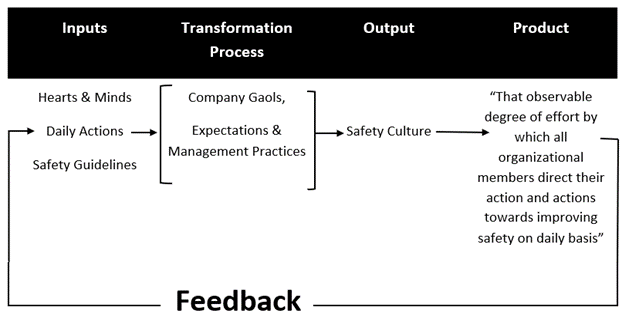

Building on his Reciprocal Safety Culture Model, by adding Business Process Model (Cooper 2002), Cooper shows safety culture as a product-driven by a process. He shows the psychological, behavioural, and situational aspects as inputs into the safety culture, influenced by organizational goals, expectations, and management practices to output the prevailing safety culture. See the image below for a visual representation of this model.

Cooper (2002): Business Process Model Safety Culture

Cooper’s definition of safety culture focuses on proactively setting safety goals and actively finding ways to influence employees’ behaviours towards safety positively. On many levels, Cooper’s Model shows safety culture as:

- Focused explicitly on routine activities to improve safety, and

- A variable that can be frequently and regularly tracked over time (i.e. assessing the effort that people put into improving safety)

Large-scale studies on accident prevention support the reciprocal safety culture model (Lund & Aaro, 2004). It shows that it provides a viable, practical approach for organizations to improve safety culture and performance to optimize accident prevention. The impact on accident prevention is substantial when both managers’ and workers’ behaviours are addressed simultaneously (Cooper 2006a, 2006b; 2010). The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) has formally adopted this exact approach as a standard.

[1] ACSNI Human Factors Study Group: Third report – Organising for safety HSE Books 1993